From sand to superposition: A key step toward a powerful silicon quantum computer

Whether it's our phones, cars, televisions, medical devices, or even washing machines, we now have computers everywhere. Using large computers, we solve big problems like managing the operation of the power grid, designing an airplane, forecasting the weather, or providing various forms of artificial intelligence (AI).

But all of these machines work by manipulating data in the form of ones and zeros (bits) using classical techniques that have not changed since the invention of the abacus in ancient times.

Realizing the benefits of quantum computing

The tireless technological progress of mankind is now confronting us with problems that cannot be solved even with the most powerful classical supercomputers.

To meet these challenges, we need a quantum computer. By harnessing the strange laws of quantum mechanics, we could benefit many sectors, including vaccine and drug design, financial risk management, industrial information processing, secure data and communications systems, as well as machine learning and AI.

Quantum computers store information in quantum bits, or “qubits.” A qubit can be any quantum object with two or more states—for example, a single electron that can be in a spin-up or spin-down state.

Using microwaves or laser beams, these qubits can be manipulated and even put into states that are a quantum mechanical mixture of ones and zeros—a state known as “superposition.” This versatility sets the stage for the great potential of a quantum computer.

Quantum computers can tackle computational tasks so that otherwise impossible calculations—processes that would take centuries on classical supercomputers—can be performed in hours.

But tackling the complex computational problems relevant to society will require a powerful quantum computer—a chip architecture, size, and complexity comparable to state-of-the-art classical processors.

In other words, a quantum processor that contains a large number of physical qubits, arranged in ordered arrays, or “scalable arrays.”

Building Quantum Devices

Silicon—made from beach sand—is a key ingredient in today’s information technology industry because it is an abundant and versatile semiconductor.

We are already building quantum devices made from silicon that have been created with dopant atoms—impurities from other elements deliberately added to change the properties of silicon.

We have shown how these devices can be programmed with quantum states to form the qubits for a quantum computer.

However, the roadblock so far is that qubits are very sensitive to even small imperfections in their environment, which can cause the qubit to lose its information (known as decoherence) requiring the calculation to be reset.

Our previous work has shown that qubits made from dopant atoms in silicon are very robust when exposed to environmental changes.

Now, our latest research, published in Advanced Materials, shows how to create large arrays of single dopant atoms on a silicon chip, which could form the basis of a powerful quantum computer.

The desirable properties of silicon and its dopant atoms for creating durable qubits allow the adaptation of standard silicon fabrication processes to new purposes in the dawning quantum era.

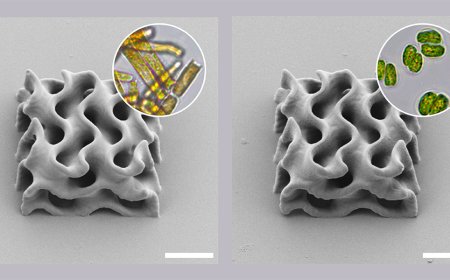

Our discovery is a way to create large-scale ordered arrays of atoms embedded in a silicon device. But not just any atoms. Our breakthrough is how to make these arrays from materials that hold promise as new qubit candidates.

Implanting dopant atoms into silicon is a standard technique for making silicon chips.

We discovered that if we equipped our silicon chips with tiny surface electrodes, we could reliably register the implantation of a single atom from the electrical signals it produced when it stopped on the chip.

These signals turned out to be surprisingly robust, allowing us to create atomic arrays on silicon devices with very high fidelity.

Now, new physical qubits, including antimony, bismuth, and germanium, offer powerful properties that provide new options for silicon quantum computers.

Creating scalable donor arrays in silicon

Our new paper shows that the technique even works for diatomic antimony molecules, in which each implantation event results in closely spaced pairs of antimony atoms.

These pairs are capable of hosting many high-quality physical qubits that can be controlled with a single electronic gate, known as "multi-qubit-gate-operation."

Now that we have shown that our novel technique works, the most important next step is to build a quantum processor from the atomic arrays configured with the necessary circuitry to program and control the qubit interactions.

The ability to create scalable atomic arrays developed from well-established industrial-production tools adapts silicon, the most important material for classical computing, to create reliable quantum computers.