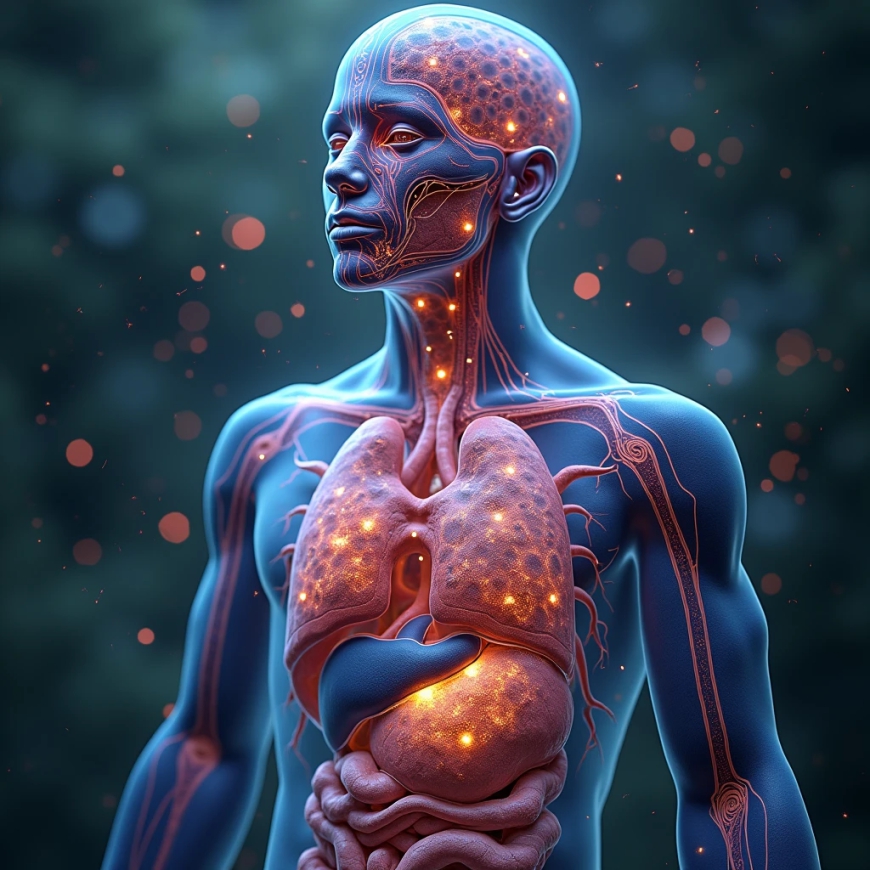

Not only the brain, but the cells of the body have memories

Most people's conceptual memories are stored only in the brain. However, a recent study has changed this idea. New research has revealed that not only the brain can 'remember', but also cells in other parts of the body. This amazing discovery was made by a group of scientists from New York University or NYU. They say that 'non-brain' cells can remember memories just like brain cells. Non-brain cells are also known as non-neuronal cells, which are not essentially neuron cells of the nervous system.

The breakthrough discovery opens new avenues for improving human learning and memory-related treatments. Because the brain is traditionally associated with memory and human learning. Especially brain neurons or its cells.

The NYU research team, led by researcher Nikolai V. Kukushkin, investigated whether different cells outside the brain have the ability to store memories.

The research was published in the scientific journal Nature Communications. In the study, the researchers looked at nerve and kidney tissue, two types of cells in the body.

The researchers exposed these two cells in the body to different patterns of chemical signals to simulate human learning.

This is similar to how different neurons in the brain respond to neurotransmitters when people learn something new. In this case, surprisingly, these cells of the body respond by producing 'memory genes' - the same genes that are activated during the storage of memories in different cells of the brain.

Researchers have used a clever way to track the working process of this memory gene. They modified these cells to make a luminescent protein, which would light up when the memory gene was activated. Through this, researchers can understand when these cells 'remember' chemical signals.

Based on how these cells of the body received the signals, these cells responded differently, the science-based site Norridge wrote in the report.

When these chemical signals are given intermittently, that is, in steps, the memory gene remains active for a longer period of time. On the other hand, if these signals are given at once, they are weak and last for a short time. This process is known as the 'spaced-learning effect', whereby people remember information better.

"This research could change how we think about the body's role in memory retention. "This suggests that different organs, such as the pancreas or cancer cells, can remember a person's habits, diet or treatment," says Kukushkin.

The research could lead to breakthroughs in understanding memory and the treatment of health conditions that depend on memory cells throughout the body.